notes on curiosity

after a curiosity dip during university

365+ days.

That’s the amount of time I began writing this newsletter. It does feel absolutely surreal that this amount of time has passed. It was a time I followed my passions and my curiosity.

But I’ve been feeling strange.

A feeling of viewing my passion as uninteresting, as if it should never have been a passion in the first place.

A feeling of viewing any action as fruitless.

A feeling of declining curiosity.

I must confess that this Substack project, which has been making progress in recent years thanks to readers like you, has fallen victim to this decline, and I haven’t been feeling as energetic as I should be. But I must also admit that this energy dip doesn’t make sense.

Nearly every action I take is overall on course to creating my life’s work - a career that I’m creating with numerous passions working together to spread valuable impact.

My bioinformatics Master’s was one action.

This Substack project is another.

Not every day is problem-free. There are external circumstances that directly or indirectly affect the course and tamper with our emotions. Myself included.

But what doesn’t make sense is how months of exploration that form connections with aspects of life to provide meaning and adventure can somehow become sort of “regretful” in a short amount of time.

To explore this, I’m going to do a bit of time-travelling back to those personal growth days, trace how it all began, and on a deeper level, what it means to be curious as a polymath.

If you’ve felt what I’ve felt and want to know about curiosity, this newsletter is for you.

My Journey of Following my Curiosity

In the context of this newsletter, a better rephrasing would be:

“How I aspire to become a polymath in the first place.”

Because after all, the one quality that creates the next generation of polymaths is curiosity.

When I was working in my first-ever proper job as a newly qualified pharmacist, I became so immersed in personal development and all aspects - health, intellect, quality of life, and particularly career.

I wrote a vision for the future about my ideal lifestyle and career, delving into what I believe, why I believe, and how to achieve it.

It was a fresh new perspective on career and work.

Here are some snippets of this vision:

My business is my life’s work.

My career combines the arts and sciences together, and encompasses a whole lot of subjects together - neuroscience, computer science, music, philosophy, medicine.

I am inspired by the actions by some of the great Renaissance humans and polymaths.

I teach people about the beauty of my topic, and tell visual stories about this.

The stories evoke curiosity, humility, humour, and happiness.

Travelling is what lights me up, and I use this to explore our world. Travel is the platform where I share myself.

As I copied and pasted the extracts, I felt a slight surge of this curiosity coming back, remembering why I wrote this down, and with hope, I imagined this could be possible no matter what.

As I progressed with more personal development, things were more attuned towards my ideal career. I enrolled on programs to kickstart my creator journey, such as Dan Koe’s Digital Economics and Ali Abdaal’s Part-Time YouTuber Academy. Both programs prompted me to look back at my vision so that my creator business can be formed in accordance with it.

Everything started connecting together, the content I was consuming, the content I’ve been creating - every action I was doing from my full-time job to my side hustle was building towards my ideal lifestyle. Enrolling on my Master’s was one of the most conscious decisions because it was part of my plan, knowing full well that it required risk-taking to follow my curiosity.

When the Master’s commenced, I viewed the content with wonder at not just how interesting it was in isolation but how it fit together and with my interests. This feeling continued throughout the taught modules and the start of the dissertation.

But when it came later on, I started feeling the dip. What I once saw as an exciting project became a chore to get done. Though I managed to complete it, I couldn’t ignore this dip because I loved feeling this state, I felt this was part of my identity that I worked hard to discover and maintain through conscious introspection of my life. But it somehow declined. Even as I’m writing this, I still don’t feel my optimum.

How do I plan to revive my curiosity?

This is where the next section of this newsletter comes in: what it means to be curious particularly as a polymath where curiosity is the one ingredient that is bringing the hype.

It starts with the damn phone

Well for me, it’s the damn iPad.

Last week I spent on average 1hr 1min daily on my phone, but spent 3hr 54min on my iPad! And I think you know who the prime culprits are:

Instagram and YouTube…

In the morning.

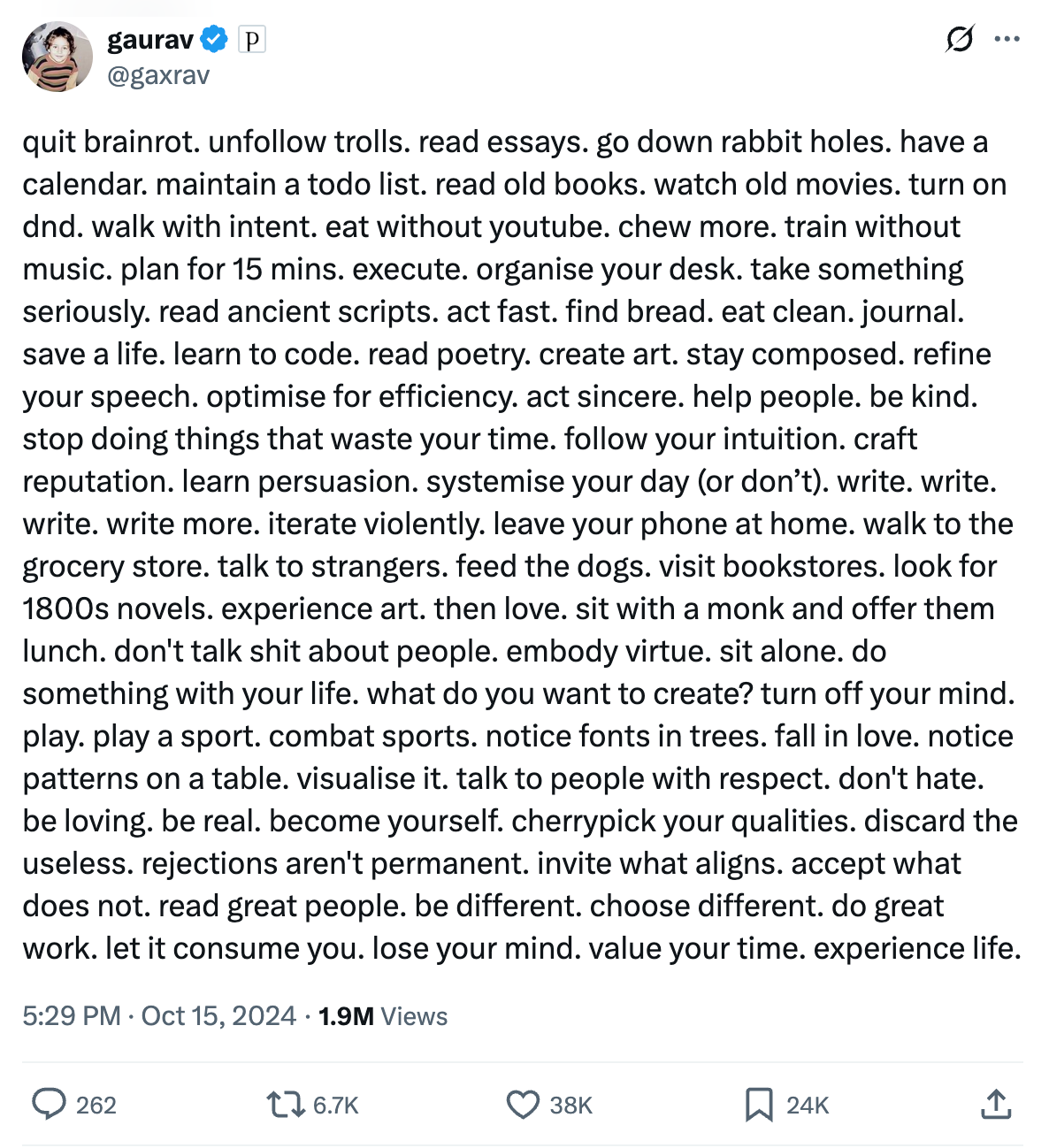

Now don’t get me wrong. They’re not inherently bad apps, and to be candid, I found creative ways to use each app. But overall, I’ve fallen into the brainrot and falling behind traps that these apps perpetuate. Both of these traps have gained a respectable amount of attention to avoid particularly this one tweet:

When it comes to curiosity, there is certainly a link. The clue is in the definition of brainrot:

A perceived loss of intelligence or critical thinking skills, esp. (in later use) as attributed to the overconsumption of unchallenging or inane content or material.

The Devil is in the Quality of Details

The “inane” or trivial content consumption is an obvious but overlooked source behind the brainrot-associated decline in curiosity. It’s obvious because the content is entertaining most of the time, and overlooked because we subconsciously underestimate the downstream impacts on our deep human psyche.

This is quality of information being discussed, not quantity.

We overestimate the quantity of information consumed, but underestimate the quality.

In 2024, I read the book Amusing Ourselves to Death by Neil Postman, and I can say hands down it’s one of the few books that completely changed how I see information. Written in the 80s, it describes how the significant flow and speed of information caused a big shift in public discourse and interpretation of issues. It was inspired by Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan and his manifesto:

The medium is the message

In other words, the message and meaning of information being consumed is dependent upon which medium it originates, e.g. book, podcast, TikTok. If you think about, each available medium in existence have different communication guidelines to comply with. If you’re writing a research article, a set structure of introduction, methods, results, and discussion is applied. If you’re making a YouTube video of the same topic, eye-catching storytelling devices like a hook are called for. These communication styles present different presentations of an issue, and are somehow commensurate with the quality and human value to be used to take creative action.

Many creators have been inspired by Marshall McLuhan and Amusing Ourselves to Death, and they alarm about the consequential minimal quality of information on social media and instead recommend higher quality media like books, which are not only longer-form but require hours of research and coaching.

But to take it up a notch, read a breadth of books and go deep:

What set great presidents apart was their intellectual curiosity and openness. They read widely and were as eager to learn about developments in biology, philosophy, architecture, and music as in domestic and foreign affairs. They were interested in hearing new views and revising their old ones. They saw many of their policies as experiments to run, not points to score. Although they might have been politicians by profession, they often solved problems like scientists.

Adam Grant, Think Again

Incorporating breadth and depth leads to more than just solving your brainrot issue, but skyrockets your curiosity.

Curiosity is the Prerequisite for Critical Thinking (and to become a Polymath)

Then comes the “unchallenging” part of brainrot consumption, signalling to a shunt in thinking critically about the information consumed, particularly on short-form content explaining about a issue with some added exaggeration.

As I was writing this piece, I came across a fellow author and polymath passionate who had a special take on critical thinking. On its own, it is designed to “fact-check, spot biases, and cross-examine arguments,” and to add to that, find the origins of arguments. But my friend describes critical thinking as a mere “filter,” critiquing how it was taught in school as only to maintain logic in debates and not for independent judgement. What she advocates instead is conceptual thinking. She describes conceptual thinking as:

the capacity to understand and integrate complex ideas, recognize relationships between diverse elements, and think abstractly about situations or problems. Leaders who leverage conceptual thinking can simplify complexity, forecast trends, and innovate by connecting seemingly unrelated information.

And she makes an important distinction between these two thinking styles. Conceptual thinking adds the following three ingredients:

Context

Complexity

Curiosity

We already touched upon context and she acknowledges complexity, but why would curiosity upgrade our critical thinking?

Adopting curiosity adopts open mindedness with the breadth and depth of topics we talked about, but it is also a catalyst to revising our personal biases that critical thinking is designed for.

When people learn to engage with their own knowledge states in more curious, open-minded, flexible ways, then we dispositionally teach ourselves to check our assumptions, to rethink what we think we know, and, and this is key, developmentally, to notice when we need to do that and when we should just play ahead…

Dr Mary Immordino-Yang, the director of the USC Center for Affective Neuroscience, Development, Learning and Education (CANDLE).

With the utilisation of breadth, depth, and integration of skills and passions, we train our minds to stay open to newer insights, and treat solving problems like play.

That is why we should never be afraid to pursue curiosity in the face of a fast-paced modern society.

I think it is just a natural extension of wanting to understand how the pieces fit together.

And not just how they fit together, but how they fit together coherently and make sense as to why they fit together that way. I think that is called congruency?