A Solution to Solving Problems of the Wicked World

Underreported but on the rise

The world is complicated.

Very complicated.

Even as I use this simple adjective, I’m thinking,

*How did we end up like this?*

All the problems and puzzles surrounding natural and technological air are desperate for **not just** our attention but the entire organ between our ears…

The whole cognitive architecture of neurotypical and neurodiverse alike.

They may be irrelevant in some cases, but they cry for help.

Help to solve the problem **effectively.**

Now I know I’m giving the problems sentience, but I think this is a decent analogy and reality of what we face today and forever.

Welcome to the Wicked World.

Before continuing, I highly recommend you explore my previous pieces, where I elaborate on the Wicked World and its impact.

To summarise for you:

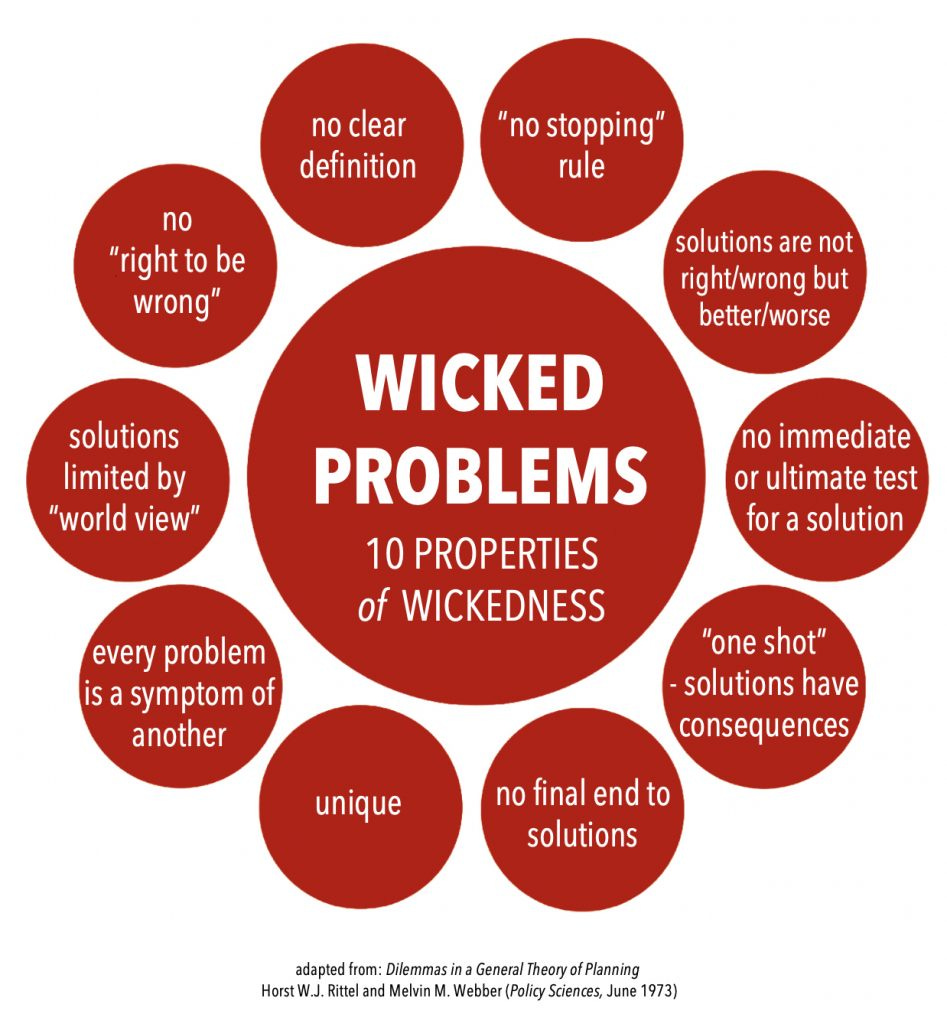

Which feature stands out to you?

What solution can you think of?

(I may have given you a clue related to our thinking).

With awareness of the Wicked World, there is one significant idea, proving to be an exciting revolution.

And it is an idea you may not expect.

Interdisciplinary curricula

As we speak, they are on the rise.

The Origins of Interdisciplinarity

Researching the history behind interdisciplinarity has not been easy, and the sources have not been so consistent in describing it.

But I found one credible candidate that can explain it.

First off, what is interdisciplinarity?

Interdisciplinarity is the process of integrating various subject areas and their perspectives and synthesising new concepts from these perspectives to approach problems.

You are searching for potential relationships between domains.

This is key.

Connecting ideas together not only improves memory retention but also clarifies why certain concepts exist, their effects on each other, and of course makes learning a lot more fun.

Now back to the history…

This thesis was written by James Welch, who works as the Interim Director for the Association for Interdisciplinary Studies, an organisation that represents scholars, teachers, and the general public who implement interdisciplinarity to address complex questions.

He enlists the epistemological contributions of Western thinkers, ranging from the fundamentals of Plato to the structuralism of Foucault.

It starts with three concepts that lack the power to solve interdisciplinarity due to their reductionist goals:

Determinism

Determinism describes the events from our own actions and decisions being [pre-]determined by causes, such as DNA and the environment. This is where philosophers can ignite a fiery debate about free will.

The crucial component of this particular cause-and-effect worldview is predictability.

As a hypothetical example, if a gene codes for a behavioural phenotype or action, probabilities can be calculated leading to predictions on when this person may commit the action again, or can be passed on to the next generation.

Welch argues that the complex nature of interdisciplinary is “irreducible,” leading to the notion that each subject domain contributes to cause-and-effect but not as absolute causes. There is a form of complex interaction that makes predicting the cause-and-effect phenomenon difficult to calculate.

Dualism

Dualism refers to the binary perception of seeing different concepts as distinct or “mutually exclusive.”

This one is easier to understand, as it disregards the notion of conceptualisation, hence complexity.

Absolute truth

The name is apt.

And as you can tell, Welch argues that interdisciplinarity is more relative.

These three worldviews may spark some controversy, but you can see where they are coming from:

They are methods to convert complexity into simplicity, but they do so by defining conceptualisation as a means to an end, so we can be satisfied that we have found the truth.

Welch summarises how interdisciplinarity is a call on how we should approach knowledge:

The complexity of knowledge is suggested by the current rhetoric of description. Once described as a foundation, or linear, structure, knowledge today is depicted as a network, or a web, with multiple nodes of connection nodes of connection and a dynamic system.The metaphor of unity, with its accompanying values of universality and certainty, has been replaced by metaphors of plurality, [and] relationality, in a complex, world. Images of boundary crossing, and cross-fertilization, are superseding images of disciplinary depth, and compartmentalization. Isolated modes of work are being supplanted by, and alliances. And, older values of control, mastery, and expertise, are being reformulated as dialogue, interaction and negotiation.

This is only a little snippet of the thesis, which I found the most intriguing and I plan to write a separate piece dedicated to the origins.

The Present Day

Our journey with interdisciplinarity continues with another academic philosopher named James.

The late James Flynn.

He is known for the Flynn effect, a reported increase in standardised IQ test scores from generation to generation, leading to his popular psychology notion that people are getting smarter. This optimism has spread in his books, a popular TED talk and a dedicated chapter in Sunday Times Bestseller, Range by David Epstein.

From his work and conversations with Epstein, Flynn echoed the experiments carried out by psychologist Alexander Luria, where he assigned two groups of farmers (remote and collective farmers) a task to categorise skeins of wool. The collective farmers were able to segregate the skeins by colour, a category of their choice, but the remote farmers refused. They were unable to find any contrasts between the wool. The contributing factor behind these findings was the work environment the farmers were exposed to; collective farmers had more modern exposure than remote farmers.

Modern life requires range, making connections across far-flung domains and ideas. Luria addressed this kind of "categorical" thinking, which Flynn would later style as scientific spectacles. "[It] is usually quite flexible," Luria wrote. "Subjects readily shift from one attribute to another and construct suitable categories.

They classify objects by substance (animals, flowers, tools), materials (wood, metal, glass), size (large, small), and color (light, dark), or other property. The ability to move freely, to shift from one category to another, is one of the chief characteristics of 'abstract thinking.’

Pay attention to the term “abstract thinking.”

Abstract comes from the Latin word “abstractus”, literally meaning “drawn away.”

So abstract thinking is the mental model of condensing information into concepts and utilising them away from closely connected observations. For example, with skeins of wool, categorisation can be colours, species of sheep, and countries of origin.

Some are obvious, others are not.

If we get the obvious categories, that’s a good start.

If we get the obscure categories, now we’re talking.

And the big obscure categories are in the form of other topic domains.

In his TED talk, Flynn further states other forms of abstraction:

1. Classification - which we just talked about

2. Logic by abstractions

3. Hypotheses

Notice how this is simplifying information but not reducing it:

We’re not disregarding perspectives in favour of others.

We’re finding connections and condensation.

However, Flynn alarms about the education system’s specialisation route to adapt to the modern world.

From Epstein’s book, Flynn conducted a study to assess students from a variety of disciplines on how they can apply the concepts and critical thinking outside of their courses. Unfortunately, the students struggled greatly.

The Core Curriculum

Flynn received his PhD from the University of Chicago and recalls the Achilles’ heel that his prestigious academy suffered from:

The lack of critical intelligence.

Students come prepared with scientific spectacles, but do not leave carrying a scientific-reasoning Swiss Army knife.

But Chicago is a special place:

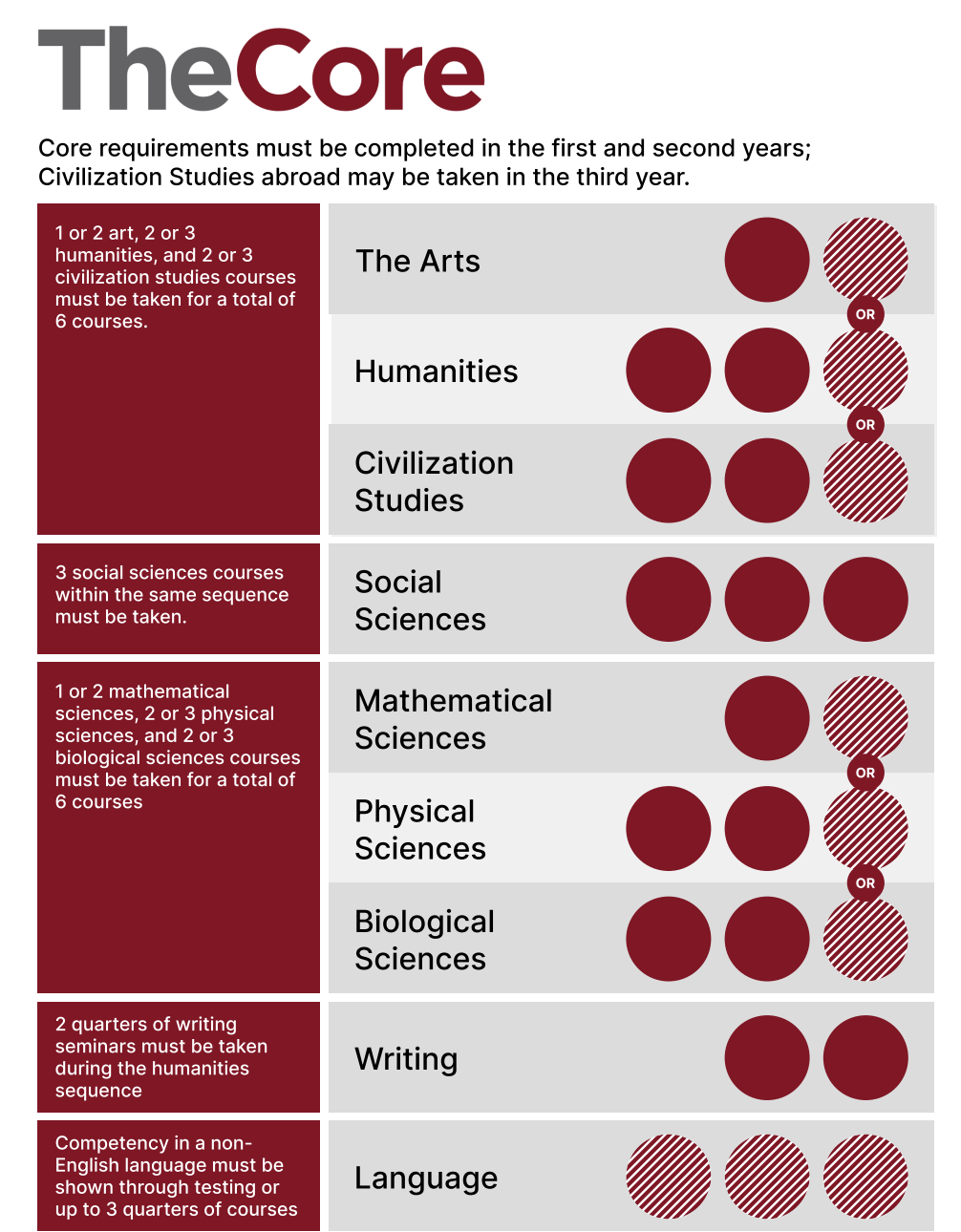

It is the home of an interdisciplinary Core curriculum.

The program, a.k.a The Core, “teaches undergraduates how to think critically and how to approach problems from multiple perspectives.”

It encompasses all areas of study, each one offering compulsory courses to take.

The Core emphasises one method to help organise critical thinking:

Writing.

It’s one of the most effective tools to assist your thinking, whether it’s through journalling or writing Substack posts, it forces you to write in your own words.

This is a great start - not many universities offer an essential thinking method, especially when you are discussing important social issues.

But we can’t ignore Flynn’s warning.

[Everyone] must be taught to think before being taught what to think about.

A Revolutionary Curriculum Emerges

The Core Curriculum has opened the door for unique education, but the specialised content from each domain can be a trap to defeat the purpose.

Chicago is not the only city to host this unconventional method.

The UK is home to a host of interdisciplinary courses:

Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (PPE)

Physics and Music

Computational Cognitive Neuroscience

Bioinformatics (which I’m studying at the moment!)

However, London has followed suit with the interdisciplinary curriculum in a new school known as:

London Interdisciplinary School (LIS).

I discovered LIS through Waqās Ahmed, the author of The Polymath, and an assistant professor at the university.

But they are unlike Chicago.

They teach by problem-solving.

It is similar to the compulsory social sciences courses in Chicago, but they focus on the methods themselves.

These methods include:

1. Scientific Method

2. Visual media

3. Programming

4. Storytelling

5. Statistics

To address the world’s challenges, we must nurture people able to confront and tackle complex problems and future leaders who understand the arts, humanities and sciences.

Professor Carl Gombrich, Dean of LIS

In addition, LIS adds two core modules to support these methods:

Complexity

All of these interdisciplinary skills are used to solve a problem, focusing on the Wicked World, filled with complex dynamic systems. To put it simply, this framework describes how systems change over time, especially with our information.

Integration

I spoke about this in the past, but there can be no denying that interdisciplinary methods and concepts require connections leading to the synthesis of new approaches.

A revolution is here.

And it’s only just begun.

Academia is becoming cognisant of modern world complexity.

These curricula are an example of this awareness.

Do you feel this the natural way we actually work. Until it’s educated out of us and then we are forced to pick a lane in our careers. I have been fighting to be a generalist for 30 years when they forced me to take specific subjects in high school and continually since.

Love seeing this becoming more recognized and accepted. Even better, being taught as curriculum.